Suicide Prevention in Primary Care: How PCPs Can Support Youth

Please Note: Suicide is a triggering and upsetting subject for many. If you find yourself in a mental health crisis and need additional support, call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988, or text Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

Suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death for youth between 10 and 24 years old, both in the United States and across the world. In fact, more young people die by suicide than the top 17 leading medical causes of death combined. Even preteens (ages 8-12) are affected by suicide, which is their 5th leading cause of death. Certain populations are especially at risk for suicide, including American Indians, Alaskan natives, LGBTQ+ youth, neurodivergent individuals, and those who are in the foster care system.

The majority of youth who go on to die by suicide are in contact with a healthcare provider before their death. 80% of adolescents visited a healthcare provider in the year before their suicide, and 49% visited an emergency room within that same time. 38%—almost half—had contact with a healthcare system in the 4 weeks prior to their death, and 34% of people 15 or older had contact with a provider in the week before their suicide. These percentages are incredibly sobering; they represent real lives of children and teens who are no longer with us.

Pediatricians report similarly high statistics of suicidal teens, with 92% of them reporting that they've had a young patient disclose thoughts of suicide. 80% of pediatricians have had a patient attempt or die by suicide—that's 8 out of 10 pediatricians. Despite this high number, 39% of pediatricians are not consistently screening for suicide risk, and only 27% of those who are screening are not using suicide-specific measures. This means that youth with suicidal ideation may accidentally slip through the cracks.

As a pediatrician or other primary care provider who cares for youth in your practice, we know you're busy. It's hard to think about screening for one more thing, but that one thing could change the course of a child's life.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends thinking about it like asthma. Most pediatricians and other PCPs are not pulmonologists, but you see young patients with asthma and help them manage their symptoms. If their case is particularly complex, you would refer your patient to a pulmonologist.

Screening for suicide risk and managing these young patients in your practice can be handled similarly; and whether or not you're screening for it, youth are struggling with suicide. You can make a difference during your routine visits with pediatric patients—and here's how!

How to Support Suicidal Youth in Primary Care: Step-by-Step

The information in the following section is directly based on recommendations made by American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

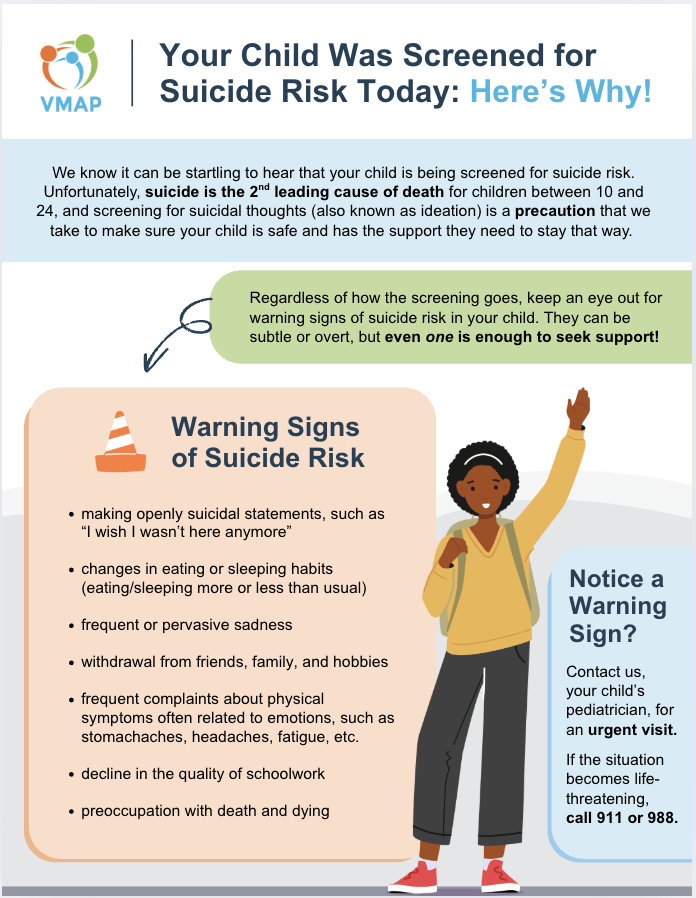

We have also created a handout for you to print and share with the parents of your pediatric patients, based on what was needed when a large pediatric practice in Richmond, Virginia implemented suicide risk screening. Parents of the pediatric patients had more questions than anticipated, so the front desk pre-emptively passed out flyers that explained the addition of suicide risk screening and the reason behind it. Feel free to print this flyer and pass it out to patient’s families as you screen for suicide risk.

1. Screen for suicide risk using a validated screening tool.

Not all screening tools are created equal. You may have heard that you can use the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) or similar tools to screen for suicide in adolescents, but that is not true. It's validated to screen for depression, but it's actually been found to under-detect patients who go on to die by suicide. One study found that using only the PHQ for suicide screening missed 32% of pediatric patients who were at risk, because not all youth who die by suicide have clinically significant depression.

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) is a great screening tool to use for assessing suicide risk. It can be used alongside the PHQ-9 Adolescent version for a well-rounded screening of depression and suicide. Here are the AAP's recommendations for when it's appropriate to screen for suicidal ideation:

- Under age 8: should not be screened for suicide risk unless there are clear warning signs

- Between 8-11: should only be screened when clinically indicated

- 12 and older: should be universally screened at every visit

2. Manage a positive screen by assessing the risk level.

A positive screen for suicide risk is not necessarily an emergency. It’s common for youth to have suicidal thoughts, but never have these escalate to suicidal behaviors. There are three levels of risk to distinguish between after a positive screen – low, moderate, and severe. When you use the ASQ screening tool, it will help you differentiate whether you have an acute positive screen (i.e., severe risk) or a non-acute positive screen (i.e., low/moderate risk).

The AAP indicates that if any level of suicide risk is detected on the screener or during a confidential discussion, you will need to notify the parents. If you have concerns about navigating confidentiality with suicide risk, visit AAP’s article “How to Talk about Suicide Risk with Patients and their Families”.

3. Implement the appropriate intervention.

The following interventions for low, moderate, and severe risk situations are taken directly from the AAP's "Strategies for Clinical Settings for Youth Suicide Prevention", which you can visit to learn more. You can also learn more about how to implement safety plans and lethal means safety counseling with AAP's article, "Brief Interventions that Can Make a Difference in Suicide Prevention".

1. Low Risk: Patient is deemed low risk with a non-acute positive screen. They receive resources and possible mental health referrals for the future.

-

- Determine if the patient might benefit from a non-urgent mental health follow-up.

-

- Send patient home with a mental health referral if indicated.

-

- Provide parents, caregivers, and families with resources to support them:

-

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline / 741-741 Crisis Text Line

-

- NAMI: Family Members & Caregivers (they have support groups across Virginia!)

2. Moderate Risk: Patient requires further evaluation but is not at imminent risk.

-

- Refer the patient to an outpatient mental health provider when clinically indicated.

-

- Conduct safety planning with the family and counsel about reducing access to lethal means.

-

- Make a safety plan with the patient and parent/caregiver that can be activated as needed.

-

- Provide parents, caregivers, and families with resources to support them:

-

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline / 741-741 Crisis Text Line

3. Severe Risk: Patient is at imminent risk and needs emergency intervention.

-

- Explain to the patient that their safety is your number one priority and that you are going to keep them safe while you figure out how to get them the help they need.

- Explain safety precautions, and ensure the patient understands that these measures are being taken to protect them, not to punish them.

- Do not leave the patient alone in the room, and ensure someone escorts them to the restroom, if needed.

- Find out if the patient has a mental health clinician they are in treatment with. If they do, ask permission to reach out because they may already have a safety plan in place, which could help avoid an unnecessary visit to the ED.

- If there is not an onsite mental health professional embedded in your practice, transfer the patient with an escort to the ED, community mobile crisis team, or acute mental health evaluation center for emergency evaluation.

- Conduct a follow-up phone call check in with the patient and their family after stabilization in an ED. The provider can phone the patient within the next 72 hours to inquire about mental health treatment linkage.

No matter what risk level your patient is, you can call the VMAP Line to connect with a child & adolescent psychiatrist or a licensed mental health professional to consult with you about your patient's case and determine the best course of action. We also have care navigators available, who can work directly with your patient and their family to find resources and follow up to ensure they connect with support services.

AAP Articles for Further Reading